This article was originally published at the defunct Skepticblog.org on April 13, 2010. An archived version is available here.

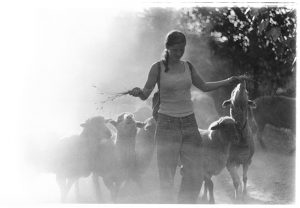

Jolene leading 1500 sheep. (Photo by Daniel Loxton.)

A very old friend of mine came into town over the Easter weekend. I went to elementary school with Jolene, and much later she was an apprentice shepherd on my crew. After a few seasons she became a Project Manager with a crew and flock of her own. My wife was a shepherd on Joe’s crew, as was our current upstairs neighbor Julie.

We only see Joe once a year or so now, so it’s always a bit of an occasion. We cracked a few beers that evening and it soon became a sheep camp reunion. And, that brought us to a small moment of skeptical reflection.

I’m going to ramble through sheep camp on my way there, though. You can skip to the end if you’re impatient.

Like other such small groups united by a hard-to-describe common experience, shepherds love to get together and tell old war stories. “Remember the time you charged those grizzly bears?” “Remember when whatsername took three hours to fail to make fire?” You know how it goes. Sheep herding was an odd sort of life: lonely yet close; boring yet stressful; peaceful yet dangerous. It sounds sort of dreamy and pastoral (and it could feel that way occasionally) but herding 1500 sheep on foot is hard work.

Most of all, it was exhausting. We worked seasons of about 90 days, plus six weeks of pre-season and a couple weeks of post-season. Work days ran 16 hours. (Easy to do, in one sense, up there along the Alaska Panhandle: in June, it didn’t really get dark till midnight.) One day off per week, if possible: the needs of the animals came first. (I recall I went five weeks one time.) Sleep deprivation was a serious issue. People can get into real trouble when they’re sleepy — particularly driving those active logging roads and lonely highways, as we had to do for supplies and equipment.

Daniel Loxton as a young shepherd. (Photo by Dennis Loxton.)

The great saving grace is that sheep rest partway through the day. They fill up all morning, and then sit down to ruminate for a while and take it easy. That’s when you get some sleep. You find a spot that’s somewhat sheltered from rain or sun (if you can) and then you just drop like a puppet with its strings cut. Sometimes you wake up in a puddle.

Today, at the ripe old age of 35, I’m retired from the sheep — but my little boy can’t get enough of those old stories. When I tuck him in at night, his “one more story” requests usually sound like this: “Dad, can you tell me the story about the one mean sheep? Please?”

Now, sheep are bright and interesting animals. Scoff if you like, but there it is. By and large they’re pleasant-tempered animals as well. But they display variations of personality, as do other complex mammals. In a flock of 1500, there are always a few bad apples. (At the beginning of every season we’d watch for those bad apples — the ones going right when everyone else is going left — and we’d put bells on them. Then, we’d know what mischief they were getting up to, even when we couldn’t see them.)

Early one season I met one of those bad apples in a most surprising way. I was asleep near the flock, nestled into a little hollow, when I suddenly woke with an agonized “Oooof!” I snapped upright, swearing, and saw a big brockle-faced (multi-colored) ewe standing near me. She stared at me, seemingly with deliberate, hostile disdain. Then, she tossed her head and strolled back into the flock.

“What the hell was that?” I asked. Not far off, Jolene was laughing in shocked disbelief. “She came right out of the flock,” Joe said, “walked right up to you, reared up, and nailed you with both front feet!”

I can tell you, that’s no joke. Big ewes run a couple hundred pounds, and they’re strong, too. This was an extremely memorable misadventure, and my son loves this story. I tell it often. (By way of epilogue, incidentally, we found that sheep and put a bell on her. We also gave her a name. Will you think less of me if I tell you she was named for the meanest girl in our Junior High school?)

Which brings us back to our shepherd’s get-together the other night. It happened that Jolene told that very same story. This was the first time we’d synchronized our memories of that event in a few years, and the outcome was inevitable: there was significant drift. The basic plot was the same — sheep comes out of flock, deliberately kicks me while I’m down — but the details were different. It was a different area, maybe a different year. In her version I was sleeping out on a skid road, not in a hollow. Little things, but big little things.

The other stories we told were the same way. Some diverged. Others just seemed a little too perfect. Did they really happen that way? Listening to the stories — telling the stories — we couldn’t be sure. Not really. Not any more.

Of course, none of this is surprising stuff for skeptics. We know memory is extremely unreliable, malleable stuff — less like a hard drive, and more like leaves floating on a pond. Whenever I hear a paranormal witness tell a tale set decades in the past, I think, “Man, I’m lucky if I can remember what happened on Tuesday.”

And yet, no matter how aware of it we think we are, we forget how much we forget.

For an interesting discussion of the unreliability of memories about memorable events, check out Daniel Greenberg’s Applied Cognitive Psychology article “President Bush’s False ‘Flashbulb’ Memory of 9/11/01” (PDF).