This article was originally published at the defunct Insight blog at Skeptic.com on Dec 11, 2015. An archived version is available here.

Painting by Daniel Loxton, c.1999. Acrylic on canvas. 24″x36″.

Skeptics naturally share this interest.

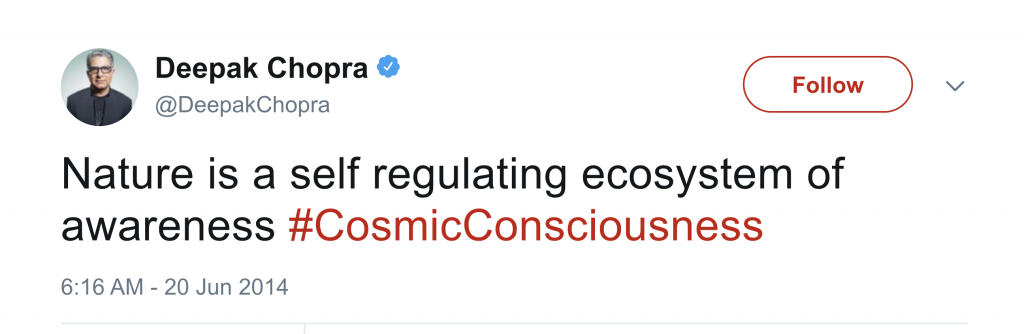

The studies presented survey participants with vague, conceptually meaningless, buzzword-laden statements and asked them to rate the “relative profundity of each statement on a scale from 1 (not at all profound) to 5 (very profound).” The included statements were generated by two online tools: “The New Age Bullshit Generator” and Wisdomofchopra.com, which “constructs meaningless statements with appropriate syntactic structure by randomly mashing together a list of words used in Deepak Chopra’s tweets (e.g., ‘Imagination is inside exponential space time events’).”2 Some of the studies also included motivational aphorisms, simple factual statements, and actual tweets selected from Chopra’s Twitter feed,3 such as this one:

Participants were also asked to complete questions designed to assess their verbal intelligence, numeracy, cognitive biases, and “epistemically suspect beliefs”—paranormal beliefs, conspiracy theories, and acceptance of claims from so-called alternative medicine—among other variables.

The punchline is that some people do seem predisposed to more readily accept vague “pseudo-profound bullshit” as valuable or meaningful than do other people. Moreover, the tendency to over-value meaningless baloney was associated with other tendencies in these studies, including paranormal belief. Simplified descriptions of these results have been been trumpeted across blogs and social media under smug headlines such as “Study Finds People Who Fall For Nonsense Inspirational Quotes Are Less Intelligent.”

I’ll leave it to better qualified writers to analyze this interesting research. But I might share a thought or two about the implications for scientific skepticism. First, I’d caution self-identifying skeptics to be on guard against uncritically accepting the ego-stroking notion that skeptics are smarter than other people—a warning Steven Novella also raises in his take on the paper. Not only is that an ugly sort of temptation, but please note that this research did not assess subcultural skeptics in any sense. Also, we’re talking about complex, dynamic human phenomena, not picking teams. As always, it’s complicated.

For example, this research found an inconsistent relationship between the kinds of far-out beliefs that scientific skeptics study and participants’ ability to discriminate between conceptually meaningful motivational slogans and meaningless profound-sounding gibberish. “This measure,” observed the authors, “was related to analytic cognitive style and paranormal skepticism. However, there was no association between bullshit sensitivity and either conspiratorial ideation or acceptance of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM).” [Emphasis added.]

Moreover, some correlation between acceptance of (some) paranormal claims and “pseudo-profound bullshit” does not mean that people do not also often have sensible justifications for the paranormal and other “epistemically suspect” beliefs that they hold. I’ve argued at length that they frequently do:

In my experience, the top reasons people believe weird things are not only understandable, but identical to the reasons most skeptics believe things: they are persuaded by personal experiences (or by the experiences of a loved one); or, they are persuaded by the sources they have consulted.

The large majority of people accept at least one roundly-debunked paranormal or pseudoscientific claim. Teasing apart factors at play in those beliefs is fascinating and useful, but predispositions are not the whole story. As Carl Sagan remarked, “People are not stupid. They believe things for reasons.”4

But Really, I Don’t Even…???

But despite my conviction that paranormal beliefs frequently make more sense than skeptics suppose, it’s not always easy to see how. Sometimes it’s not even possible.

Statistical difference in responses to vague statements is not the only way in which skeptics and paranormal believers may fail to speak the same language. Sometimes we feel genuinely unable to understand what the hell the other is talking about. We can see that it’s meaningful to the other person, sense that it’s self-evident from their point of view. We can see that it matters to them. But it just seems… we struggle to… and then we give up.

You may feel this disconnect sometimes with paranormally-inclined friends, neighbours, and family members. Certainly I feel it when reading certain works by paranormal proponents. Some beliefs are easier to sympathize with; some are just too hard. I’ve advocated for the value of the intellectual vertigo we may experience if we manage to truly feel the persuasiveness of the other person’s belief—to “catch a glimpse of the Goblin Universe,” as it were. But sometimes we can’t. We may want to see what the other person sees. But it just looks like gibberish, like a “Magic Eye” composition that refuses to resolve into an image.

It’s disconcerting how wide the chasm of language and foundational assumptions may sometimes prove between two people—in a profound sense, the distance between two parallel universes. We can stand in a room with someone, converse with them, laugh, share, empathize with each other in many ways, and yet somehow still occupy worlds with differing laws of physics, diverging epistemological frameworks, even incompatible rules of logic. This alienness is unnerving, and from a communications perspective, daunting. How can anyone bridge such deep conceptual divides in any practical amount of time? We rarely get more than a few seconds to reach someone in a blog post, outreach message, or everyday personal exchange.

The skeptical literature contains many contributions from people who have taken this challenge seriously. A great place to start is Karla McLaren’s 2004 Skeptical Inquirer article, “Bridging the Chasm Between Two Cultures.”

It’s vital that a way be found to help people in my [New Age] culture question, think about, and critically interpret the barrage of information and misinformation they receive on a daily basis. However, it’s also vital that the information be culturally sensitive. … I know firsthand that the skeptical viewpoint cannot [currently] be heard or assimilated in the New Age and metaphysical community; it is anathema, and that’s a shame for every single one of us.

Other noteworthy discussions in this vein include astronomer Phil Plait’s “Don’t Be a Dick” speech (video), psychologist Ray Hyman’s influential essay “Proper Criticism,” and of course Carl Sagan’s Demon-Haunted World. Sagan returned to the theme many times, advising skeptics to “temper our criticism with kindness.”5 Aaron’s World producer Mike Meraz contributed a worthy grassroots effort with his short-lived program Actually Speaking, a podcast which explored “the human side of skepticism…from an interpersonal perspective”—that is, a communication primer for skeptics. All advised speaking softly and listening hard.

It should be understood that none of these contributions “solved” the problem in any ultimate sense. The truth is that it’s difficult to effectively communicate ideas, especially if those ideas challenge deeply held beliefs. These writers have instead tended to focus on communication’s “easy” problem: removing unnecessary obstacles to understanding, and avoiding willful alienation of the very people one wishes to reach.

References

- Gordon Pennycook, James Allan Cheyne, Nathaniel Barr, Derek J. Koehler, and Jonathan A. Fugelsang. “On the Reception and Detection of Pseudo-Profound Bullshit.” Judgment and Decision Making, Vol. 10, No. 6, November 2015, pp. 549–563.

- Ibid.

- Ibid. The authors add, “We emphasize that we deliberately selected tweets that seemed vague and, therefore, the selected statements should not be taken as representative of Chopra’s tweet history or body of work.”

- Carl Sagan. “Wonder and Skepticism.” Skeptical Inquirer. Volume 19.1, January / February 1995. As republished at http://www.csicop.org/si/show/wonder_and_skepticism

- Carl Sagan. The Demon-Haunted World. (Random House: New York, 1996.) p. 298