This article was originally published at the defunct Skepticblog.org on May 25, 2010. An archived version is available here.

By now you will most likely have heard the sad news of the death of Martin Gardner — the father of modern skepticism — at age 95. He was, as his friend James Randi wrote, “a very bright spot in my firmament.”

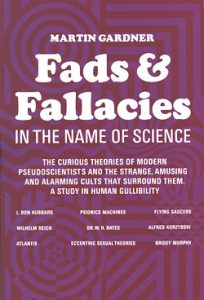

Many people feel the same way, and for good reason. Gardner’s impact cannot be overstated. It is fair to argue that Martin Gardner created the modern skeptical literature from whole cloth. His 1952 book In the Name of Science (retitled Fads & Fallacies in the Name of Science for the second and subsequent editions; hereafter referred to as Fads & Fallacies) set the standard that later led to the creation of CSICOP — and to all that has followed since. Through his books and his “Notes of a Fringe-Watcher” column in the Skeptical Inquirer, Martin Gardner was a meticulous skeptical scholar for six decades. (Amazingly, his most recent Skeptical Inquirer articles appeared earlier this year.)

I’m writing this essay about this “good old man” in long-hand, sitting at the side of a neighbourhood swimming pool. I’m watching my own young son laughing and splashing, and thinking about life: its brevity, its preciousness, its cycles of wisdom and forgetfulness and rediscovery. How fleeting it can be — not only life, but memory and understanding as well. What will my son remember of the lessons I try to teach him? What will I remember of the things my own father taught me?

I wrote recently about the dawn of the organized skeptical movement with the formation of CSICOP in 1976. Today I’m looking back further — a whopping 24 years before the founding of CSICOP or any other skeptical organization. Gardner stepped onto the stage with Fads & Fallacies the year after Carl Sagan graduated high school. James Randi was, at age 24, making a name for himself as a bright young magician. It was the year that Paul Kurtz, a U.S. Army veteran of the liberation of Dachau, finished his PhD in philosophy. Legendary investigator Joe Nickell, whose historical overview essay style follows the Gardner model, was an eight-year old boy. Many of our most respected science advocates, like Michael Shermer and Steven Novella, had not yet even been born.

For my part, my own father was three years old when Gardner invented the modern skeptical literature — with the book I dug into again this morning.

A True Classic

I never met Martin Gardner, and it’s been years since I last re-read his books. Still, returning to Fads & Fallacies is like speaking to a close old friend I haven’t seen in years. (When we were shepherds, my brother Jason and I used to carry battered copies of skeptical masterpieces in our backpacks. Sagan’s Demon-Haunted World, Randi’s Flim-Flam! and Gardner’s Fads & Fallacies were among the most important of them.)

If you haven’t read Fads & Fallacies, you should. (I mean, really, head down to your local library today. What better way to honor Gardner’s life in skepticism?) Fads & Fallacies is a revered classic, of course, and yet completely modern in style as well as substance. Its crisp chapters each review the history and arguments of a specific pseudoscientific topic (such as creationist flood geology, Atlantis, or “orgone” energy), placing the development of that topic in context with its closest pseudoscientific relatives, and contrasting it with the relevant science. Gardner’s model is followed today by Joe Nickell, by Brian Dunning’s Skeptoid podcast, and of course by my own Junior Skeptic articles.

The scholarship of these articles is extremely impressive, and very certainly worth our effort to study. For years I’ve aggressively pursued primary sources for skeptical research, building a very respectable library on these obscure topics; and yet, a few minutes flipping through Fads & Fallacies just now informed me about a half dozen obviously important volumes I didn’t know anything about. And I should know about those books. Skeptics should know as much as we can of what Martin Gardner knew, because we’re the only people who can continue and build on his research.

One of the great lessons of skepticism is that weird ideas never go away. One of the functions of skeptics is the study of the history of claims and hoaxes, so that experts are available when those claims inevitably mutate or resurge. Readers of Fads & Fallacies will learn, for example, not only what is wrong with the concept of dowsing (relevant all over again, and lethal, in the wake of the Iraq bomb-detector scandal); about the key volumes and thinkers to develop the dowsing idea through the early 20th century (and before); and also about the related idea of radiesthesia (pendulum divining, which incidentally gave birth to pyramid power).

Gardner’s Blueprint

Among its many virtues, Fads & Fallacies stands out for its clarity as a blueprint for later skeptical research, organization, and activism. I’m somewhat known for a manifesto-type essay advocating for traditional skepticism. I could have saved myself 5000 words if I’d just written, “What Martin Gardner said.”

From the first page, Fads & Fallacies is explicit about the problem it wants to address: the influence and dangers of pseudoscience. Gardner was concerned about

the rise of the promoter of new and strange “scientific” theories. He is riding into prominence, so to speak, on the coat-tails of reputable investigators. The scientists themselves, of course, pay very little attention to him. They are too busy with more important matters. But the less informed general public, hungry for sensational discoveries and quick panaceas, often provides him with a noisy and enthusiastic following.

Gardner saw this volatile combination — poor public science literacy; the existence of cranks and con men; and, the fact that pseudoscientific claims are typically left unexamined by serious scientists — as a call to action. It is a call others took up in the decades that followed. Today we call that project “scientific skepticism.”

But why should anyone care about pseudoscience? Why is pseudoscience worth fighting? In every generation, skeptics ask themselves this question — a question Gardner anticipated.

Perhaps we are making a mountain out of a molehill. It is all very amusing, one might say, to titillate public fancy with books about bee people from Mars. The scientists are not fooled, nor are readers who are scientifically informed. If the public wants to shell out cash for such flummery, what difference does it make?

Gardner offered several answers to this question. To begin with, he noted, there is a human cost “when people are misled by scientific claptrap.” He offered the sad example of mentally ill people “desperately in need of trained psychiatric care” whose treatment is delayed by “dalliance in crank cults.” (Lest you doubt Gardner’s relevance today, he was talking about Dianetics, the basis of Scientology. Fads & Fallacies includes an in-depth chapter about Scientology’s history and claims.)

I think that rock bottom truth — people get hurt — is ample reason for people of conscience to care about pseudoscience (especially medical pseudoscience). Nonetheless, Gardner provided other answers as well. One is that unchallenged pseudoscientific beliefs (even when apparently harmless) can reenforce other (perhaps more dangerous) unfounded beliefs.

What about the long-run effects of non-medical books like Velikovsky’s, and the treatises on flying saucers? It is hard to see how the effects can be anything but harmful. Who can say how many orthodox Christians and Jews read Worlds in Collision and drifted back into a cruder Biblicism because they were told that science had reaffirmed the Old Testament miracles?

(To appreciate the prescience of this comment, consider that Answers In Genesis still finds it necessary to include on its list of “Arguments That Should Never Be Used” the Velikovskian notion that the Earth stopped rotating for a day during the life of the Old Testament figure Joshua. Check out their surprisingly good debunking article on the topic of Joshua’s missing day.)

Worse, Gardner argued, pseudoscience erodes scientific literacy in general — a process as unpredictable as it is dangerous.

An even more regrettable effect produced by the publication of scientific rubbish is the confusion they sow in the minds of gullible readers about what is and what isn’t scientific knowledge. And the more the public is confused, the easier it falls prey to doctrines of pseudo-science which may at some future date receive the backing of politically powerful groups. As we shall see in later chapters, a renaissance of German quasi-science paralleled the rise of Hitler. If the German people had been better trained to distinguish good from bad science, would they have swallowed so easily the insane racial theories of the Nazi anthropologists?

Gardner’s Solution, and Legacy

What was Martin Gardner’s solution to the problem of pseudoscience? The first step is implicit in his decades of painstaking work: scholarship. To tackle pseudoscience knowledgeably, skeptics take on (to greater or lesser extents) the task of becoming scholars of pseudoscience.

This is a colossal project. Skepticism’s traditional subject matter includes hundreds of pseudoscientific and paranormal topics — each with its own literature, history of development, major figures and major works, and collection of critical responses. Sometimes, as with homeopathy or astrology or dowsing, the history of a single topic stretches back centuries. Martin Gardner researched that vast field for decades, acquiring a depth of knowledge and understanding that is unparalleled among living skeptics. It is left to each of us to fill some small, specialized part of the gap he has left.

In 1952, Gardner showed us what skeptical scholarship looks like, setting the standard that skeptical researchers follow today. At the same time, he called for the now-traditional other half of the skeptical coin: working to advance scientific literacy.

We need better science education in our schools. We need more and better popularizers of science. We need better channels of communication between working scientists and the public. And so on.

And so on. The road always continues — and eventually, the travelers do not. Martin Gardner lived to see his personal call to arms grow into a lively research field, an activism movement, and even (through skepticism’s digital renaissance) a flourishing global subculture. It’s a wonderful legacy. For a time, it is ours to preserve. And so, tonight I’ll be raising a glass to the memory of Martin Gardner — and thinking hard about the things he had to teach.