This article was originally published at the defunct Skepticblog.org on July 26, 2010.

An archived version is available here.

The Amazing Meeting (TAM) conference in Las Vegas is always the center of the skeptical universe, and TAM8 was no exception. Bigger and more representative than any previous year (it was co-sponsored by all three national US skeptics groups), TAM8 was an unprecedented summit for North American skepticism.

The Amazing Meeting (TAM) conference in Las Vegas is always the center of the skeptical universe, and TAM8 was no exception. Bigger and more representative than any previous year (it was co-sponsored by all three national US skeptics groups), TAM8 was an unprecedented summit for North American skepticism.

A lot happened. For a detailed discussion of TAM8, check out my roundtable chat with Tim Farley (What’s the Harm?), Blake Smith (MonsterTalk), and Derek and Swoopy on Skepticality [no longer available]. There’s been a lot to talk about.

Most especially, people have been talking about Phil Plait’s powerful talk, now known to the blogosphere as the “Don’t be a dick” speech (after “Wheaton’s Law,” an internet maxim that provided the theme of Phil’s presentation). In his talk, Phil argued that skeptics who have outreach goals should get serious about communication:

In times of war, we need warriors. But this isn’t a war. You might try to say it is, but it’s not a war. We aren’t trying to kill an enemy. We’re trying to persuade other humans. And at times like that, we don’t need warriors. What we need are diplomats.

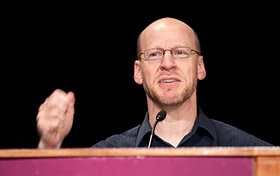

Phil Plait argues passionately at TAM8. Photo by Marc-Julien Objois

You may not be surprised to hear that I loved this speech. I think it was an important moment in recent skeptical history, and it meant a lot to me personally. “Be nice to people” is a drum I’ve been beating for a long time. I was moved more than I could express to hear someone of Phil’s stature make that case so forcefully from the big stage at skepticism’s big event.

No matter how you look at it, he is of course right: there many excellent reasons to tend toward treating people with respect and courtesy. It’s morally bad to be cruel (and usually unnecessary); it’s contrary to scientific and journalistic ethics (and the search for truth) to shout down legitimate alternate views; it blinds us to flaws in our own reasoning if we fail to seriously consider viewpoints we don’t like. Most importantly (this was the theme of Phil’s talk) science communication is more effective when it starts with warmth and respect.

Those are all excellent topics for further exploration, but my aim today is smaller. I’d like to add one more footnote to the other arguments for civility, which is this:

Many people have quite good reasons for believing in the paranormal.

Lines Through The World

Individual skeptics sometimes form an impression that paranormal beliefs are held by strange people for inexplicable reasons — but not by our kind of people. Speaking personally, I’ll confess that I’m sometimes taken off guard when someone I know turns out to believe some bizarre paranormal thing, even though I know by now to expect it.

But a simple survey of our friends, family and co-workers will often put paid to the notion that paranormal belief is uncommon or unusual. Try it. Gently ask around. If you’re like me, it’s likely that most of the people you know accept some paranormal claim: perhaps alien visitation, or ghosts, or dowsing, or psychic powers, or some form of alternative medicine. The paranormal is everywhere: in labs, in schools, in hospitals, and at your Christmas dinner table.

Faced with the ubiquitousness of such beliefs, a few skeptics are tempted to think there must be something special about those who don’t believe. That conceit hardly seems worthy of dwelling upon, and yet people have actually tried to convince me on this basis that it’s not worth teaching critical thinking. “The smart people already get it,” I’ve been told, “and the stupid people never will. Don’t waste your time.”

I suppose it’s human to want to draw these lines through the world: on this side, the good smart people; on the other side, the bad dumb people. But the world is not nearly so simple.

Raising My Hand

One of the interesting things Phil Plait did during his challenging TAM8 speech was to ask the 1300 skeptics in the room this question:

How many of you here today used to believe in something — used to, past tense — whether it was flying saucers, psychic powers, religion, anything like that? You can raise your hand if you want to.

I was one of the majority of people who raised their hands. If I could have, I would have raised my hand dozens of times for all the dozens of paranormal claims I used to accept.

Does this mean that most of the people at TAM are stupid? Of course not, and I don’t think anyone would make that argument. And yet, I quite often hear skeptics talk about “the woos” as though “they” (in practice, our own friends and neighbors) belong to some alien species.

The Reasonableness of Weird Things

But here’s the thing: most pseudoscientific beliefs are not stupid. They’re just wrong.

Consider two people, Ada and Bee. Both consider themselves critical thinkers. Both walk into a pharmacy looking for headache medication. Ada buys Tylenol, because it has been recommended by people she trusts, because she knows from experience that it works for her, and because she thinks most of alternative medicine is hogwash. By contrast, Bee buys a homeopathic remedy — because it has been recommended by people she trusts, because she knows from experience that it works for her, and because she thinks most of mainstream medicine is hogwash.

In this case, neither the “skeptical” Ada nor the “credulous” Bee has any medical training. Neither has direct knowledge of the primary medical literature about acetaminophen, nor of the primary skeptical literature on homeopathy. I submit that neither Ada nor Bee should be much applauded or scorned for their beliefs. They’re both just regular folks making regular decisions based on the best information they have.

In my experience, the top reasons people believe weird things are not only understandable, but identical to the reasons most skeptics believe things: they are persuaded by personal experiences (or by the experiences of a loved one); or, they are persuaded by the sources they have consulted.

For example, I know several people who believe in ghosts for the perfectly straightforward reason that they personally saw a ghost. They’re willing to consider alternate explanations, but c’mon: of course their personal ghost encounter leans heavily on the scales of evidence. Science may say it’s wise for Ebenezer Scrooge to suppose Marley’s specter “may be an undigested bit of beef, a blot of mustard,” but Christmas Carol audiences understand that ghost belief would be pretty reasonable under the circumstances. (And, when ghost witnesses are critical-minded enough to dig into some books or online research, the sources they find authoritatively argue that ghosts are probably real.)

This pattern comes up again and again, from the woman who shyly speaks about her alien abduction experience, to the friends who enthuse about dowsing rods, to the family members who swear by alternative medicine: “My personal experience confirms that this is true.”

Yes, reasoning from visceral experience is a recipe for false belief. Obscure research tells me that my friend is extremely unlikely to have been abducted by aliens. But she was there, and I wasn’t. I don’t know what she saw, not for sure — and I can’t deny that her experience of seeing it could make a pretty compelling basis for personal belief.

Now, I want to be clear here: I’m not suggesting that personal experience is an adequate basis for accepting paranormal claims (it isn’t) or that these claims are true (so far as science can tell, they’re not). I’m saying that, given their information and tools, many paranormalists have understandable reasons for belief.

The Difference Between Believers and Skeptics?

However we label ourselves or others, we come up against the fact that people are complicated. Generalizations are doomed to inadequacy. But, I will suggest that the differences between skeptics and paranormal believers have less to do with innate credulity, and more to do with training and resources.

When I was a scruffy young boy, I found a Bigfoot footprint in the wilderness of British Columbia. Devouring every sasquatch book I could find (there were several in my elementary school library), I learned the persuasive facts that many, many people had found footprints or reported encounters with Bigfoot, and that sasquatch photographs had even been taken. Therefore, I believed in Bigfoot.

What I did not have was any understanding of how those many witnesses could all be wrong (myself included), or how on Earth hoaxing could account for most prints. I didn’t have any access to the skeptical books or magazines (still rare today, but then vanishingly so) that could have explained it to me. And, most importantly, I did not know what I did not know. I had to be taught to ask counter-intuitive questions, and I had to be taught how to find the best answers.

I wasn’t born knowing that stuff. Nobody is. As Phil Plait’s speech put it, “Skepticism is hard.” It’s hard, and it has to be taught. And that is how it can be that several hundred thoughtful skeptics at the The Amazing Meeting 8 used to believe in magic.