This (lightly edited) article was originally published at the defunct Skepticblog.org on Jan 22, 2013. An archived version is available here.

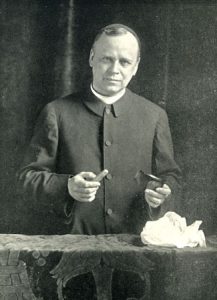

Father C. M. de Heredia shows two séance props—a false finger and a comb with a hollow spine—from which “ectoplasm” could be “materialized.”

I had a post ready to go for this morning on the topic of early twentieth century skeptical activist Joseph F. Rinn; but at a couple of thousand words, I thought it might be more appropriate for next week’s

eSkeptic. [

Read that article, republished here.] Like my last

post on the surprisingly complicated history of the skeptical slogan “extraordinary claims demand extraordinary evidence,” my current

Junior Skeptic article about second century Roman debunker Lucian of Samosata, and my next

Junior Skeptic about two especially hard core early twentieth century skeptical investigators who happened to be women, the new Rinn piece is part of larger exploration I’ve been doing of the skeptical work of the decades, centuries, and even millennia prior to 1976 (the year of the formation of CSICOP, now called CSI—a moment which is usually considered the birth of the fully modern skeptical movement).

The skeptics of previous eras faced a few wrinkles unique to their contexts. How could they not? Yet the more striking thing is how very much repeats over time. The mysteries are the much same, decade after decade, and often identical. The arguments, the exposés, the scams, the rhetoric, and the sense of unique moral urgency—of sliding into a new Dark Age—all these echo across generations. For all the fine mustaches of the early twentieth century skeptical scene (and man, those were some damn fine mustaches) these were people whose mission and challenges were much the same as my own. The sense of continuity this historical perspective brings is—palpable? illuminating? remarkable? Read more