This article was originally published at the defunct Skepticblog.org on Nov 27, 2012. An archived version is available here.

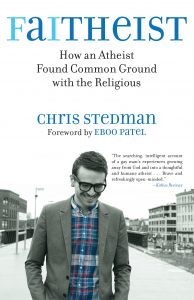

I’m drinking my morning coffee as I write this, and thinking about a moving, thought-provoking book I’ve been reading for pleasure: humanist interfaith activist Chris Stedman’s Faitheist: How An Atheist Found Common Ground with the Religious.

I’m drinking my morning coffee as I write this, and thinking about a moving, thought-provoking book I’ve been reading for pleasure: humanist interfaith activist Chris Stedman’s Faitheist: How An Atheist Found Common Ground with the Religious.

I try to follow a number of firm guidelines for my writing at skeptical platforms like Skepticblog. One is never to talk about anything unless I’ve given that thing a thorough look myself—read the book, seen the movie, tracked down the paper, whatever. Another is to keep my personal politics, humanism, and atheism out of my skeptical writing as much as possible. After all, skepticism is not a private clubhouse for people who share my personal values and opinions; it’s a shared workspace for people of many backgrounds to pursue the useful practical task of investigating fringe science and paranormal claims. (Believe this, don’t believe that—who cares? Science and skepticism are about what we can find out.)

But I’m not a robot. I believe stuff. I enjoy stuff. So today I thought I might break my own guidelines and share a few preliminary personal thoughts about an atheist book I haven’t finished reading, but which I am savoring.

Country AND Western

Like his other writing and interfaith work, Stedman’s book calls powerfully for a more compassionate, more nuanced, more accepting dialogue between people of faith and people who have none. Given the strong anti-theistic sentiments common currently in movement atheism and the atheist blogosphere, this has not too surprisingly made Stedman a somewhat controversial figure in atheist circles. Some place him as part of an established narrative—a proposed distinction between atheist “firebrands” and “diplomats.”

“We need both,” it is often said, “firebrands and diplomats.” Working together—the soft sell and the hard sell, the good cop and the bad—these complementary approaches may do more to bring down religion than either prong of the attack may accomplish on its own. “We’re all part of the same movement,” say these voices. “We all want the same thing.”

But that’s just it. We don’t all want the same thing.

The radical function of Stedman’s Faitheist is to underline that rarely-stated truth. Atheism is actually not a duopoly of firebrands and diplomats. These two types of evangelists no more describe “both kinds” of atheist than “country and western” describes “both kinds” of music.

Stedman explicitly rejects “the demise of religion”—that is not a goal he shares. He also rejects the firebrands versus diplomats dichotomy. “I believe how pushy should we be? is the wrong question,” he writes. The better question is how do we make the world a better place?

I work to promote critical thinking, education, religious liberty, compassion, and pluralism, and to fight tribalism, xenophobia, and fanaticism. Many religious people are allies to me and other atheists in these efforts—and a good number of them cite their religious convictions as the motivating factor behind their work. I am far more concerned about whether people are pluralistic in their worldview—if they oppose totalitarianism and believe those of different religious and nonreligious identities should be free to live as they choose and cooperate around shared values—than I am about whether someone believes in God or not.1

Atheists are not and never have been unified by a dislike of religion (nor especially of religious people). We atheists are a mixed population. We comprise an ecosystem of beliefs and values—some of those values in concord with the values of religious people, and some of those values necessarily in tension with the values of other nonbelievers. It simply is not the case that atheists are unified by a wish to convert more believers into nonbelievers, or to work toward a religion-free future. Some atheists do happen to want those things. Others do not.

Many atheists simply do not care whether other people have faith. Some atheists actively like religion, or suspect that it may be a net force for good for humanity, or consider the concept of “religion” too nebulous to judge. Some atheists find the concept of an atheism that seeks to persuade, to convert, or to grow its numbers to be distasteful or even morally wrong. And most common of all, perhaps, are the countless de facto atheists who live quietly secular lives without bothering themselves about god debates one way or the other.

Speaking for Myself

I’m an atheist. I’m even a fairly “hard” atheist—I feel morally certain that god does not exist. But that does not mean I’m remotely interested in convincing anyone else to agree (nor of course that I think as a skeptic that my untestable religious conviction is a demonstrable scientific fact). For me, atheism is a bit like being fair-skinned. It’s a true fact about me, but in most contexts it’s not a very important fact.

Movement atheism—atheist activism—has long been dominated by folks who think religion is a problem to be combatted and perhaps one day solved. That apparent unity of purpose is a social and historical artifact, an illusion. Antitheists are not representative of atheists as a whole. Now, when I say that, I’m not arguing that antitheism is bad. (I have reservations about confrontational antitheism, some serious, but that’s not my point at the moment.) Certainly an argument can be made that religion is a net negative for humanity; people who happen to believe that have the right to unify around that idea.

It’s just that there’s no place for me in an antitheist movement. It’s not who I am. Such a movement does not represent my values or beliefs.

Which is what makes Stedman’s Faitheist such a pleasure for me.

Looking Back

Faitheist is an argument for humanism—for the prioritizing of the wellbeing and dignity and complexity of human beings over our ideological differences—framed in the language of a memoir. Stedman’s look back over his life leaves him starkly exposed. It’s moving to read, while also reminding me (cringe-inducingly) of my own youthful struggles with faith and love and sex and existential meaning. It’s like Quantum Leaping back into my screwed up life in 1992—which is around the time that I engaged in my first public act as an “out” atheist. By coincidence, that act was interfaith dialogue of just the type that Stedman advocates today.

I participated as a youth delegate in an interfaith conference held on the beautiful, secluded campus of the United World College’s Pearson College of the Pacific. I openly attended as an atheist, a secularist, and at that time an antitheist. I arrived opposed to religion. I left opposed to religion. (Also, I was an ass. I recall that I was interviewed by a television crew at the event, and fondly hope that the tape no longer exists.) And yet, it was also an eyeopening event for me. To this day I remember conversations I had that weekend.

The goal for the conference was the drafting of recommendations for comparative religion curricula. The line I advocated was what I would advocate today: that comparative religion is an important part of every kid’s education, and should ethically be taught through a lens of secular scholarship, not partisan faith. The first is education, I said; the latter, propaganda. Well, responses to that argument, and to the task of the event, were very mixed. I found tension where I wouldn’t have expected it, and found common ground where I would not have expected that. I got to know folks better, communities better. (The kids from the Bahá’í school in Shawnigan Lake were especially interesting—smart, groovy, and from a religion I had never heard a whisper about until that moment.)

This fascinating experience had an impact (as did many others). But you know how it is. Change doesn’t happen overnight. I spent a few college years as what we might now think of as a confrontational New Atheist-style firebrand. But it didn’t stick. Over time I found myself less and less concerned about other people’s faith, and more and more inspired by the values of humanism. To this day, that is how I think of myself. I am an atheist (a mere fact); I identify as a humanist (my values and viewpoint); I do skepticism (my professional task).

Then came 2001. The 9/11 events shook a lot of nonbelievers. I mean, 9/11 shook everybody—much of humanity howled in protest—but it changed many nonbelievers. “My last vestige of ‘hands-off religion’ respect disappeared in the smoke and choking dust of September 11, 2001,” wrote Richard Dawkins. It was, he said, “time to stop pussyfooting around. Time to get angry. And not only with Islam.”2 I felt some of that anger myself. Everybody did. But the ghastly footage of smoke and dust was not the thing that defined the impact of 9/11 on my own life. What I remember is sitting on the warped, splintery wooden floor of my hallway late on the night of September 12 or 13, speaking to one of my closest friends on the phone. She and I had gone to high school together, and later worked together herding sheep in the wilderness. She phoned from Hong Kong to say her brother had died in the Twin Towers. She was flying to New York to meet her family. Would I tell our shared friends what had happened? Of course I would. “What do you think will happen now?” she asked me, half a world away. We knew the world had changed. Her world. The entire world. “The Americans are going to set a lot of people on fire,” I said, in shock. “They’re going to pick a country and level it.” All the sorrow for her loss, for all those families’ losses, was compounded by the sorrow for the losses still to come. I’ve never stopped thinking about the human cost of Iraq and Afghanistan, the losses on all sides—all those people in their thousands and their tens of thousands—nor about the more subtle costs of suspicion and racism and religious discrimination, here and around the world.

The truth is that the face of religion is not defined by suicide bombers—it is as diverse as humanity itself. Religion is firefighters and cops and volunteers coated in choking dust, soldiers serving overseas, heroes and monsters and geniuses and fools. The religious are no less complex, no less valuable than anyone else. Their sorrows and joys are all of ours.

Chris Stedman’s work calls humanists to remember that complexity. It asks us to speak first to our shared humanity. As humanism, this is unexceptional. Humanism has always had its thin vein of anti-religious sentiment, but the main theme of humanism—humanism’s beating heart—is the call to altruism, the call to value the wellbeing and dignity of every spark of human consciousness.

Stedman’s work embodies what humanism is, in my view. But he does something more when he positions his work not only as humanism, but as “atheist interfaith activism.”

He makes a place in atheism for atheists like me. Perhaps for the first time.

References

- Stedman, Chris. Faitheist: How An Atheist Found Common Ground with the Religious. (Boston: Beacon Press, 2012.) pp. 153–154

- Dawkins, Richard. A Devil’s Chaplain. (New York: Mariner Books, 2004.) pp. 156–157