This (lightly edited) article was originally published at the defunct Skepticblog.org on Jan 22, 2013. An archived version is available here.

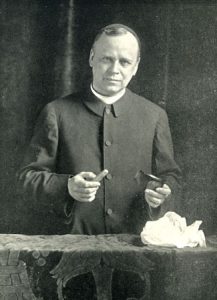

Father C. M. de Heredia shows two séance props—a false finger and a comb with a hollow spine—from which “ectoplasm” could be “materialized.”

The skeptics of previous eras faced a few wrinkles unique to their contexts. How could they not? Yet the more striking thing is how very much repeats over time. The mysteries are the much same, decade after decade, and often identical. The arguments, the exposés, the scams, the rhetoric, and the sense of unique moral urgency—of sliding into a new Dark Age—all these echo across generations. For all the fine mustaches of the early twentieth century skeptical scene (and man, those were some damn fine mustaches) these were people whose mission and challenges were much the same as my own. The sense of continuity this historical perspective brings is—palpable? illuminating? remarkable?

As my intended post has gone to another home, I’d like to share with you an amusing if trivial example: in many eras, skeptics have suggested that it may be a bad idea to investigate mysteries in the freaking dark.

In 2010, Benjamin Radford identified messing about in darkness as one of the best ways not to investigate the paranormal in his book Scientific Paranormal Investigation. You wouldn’t think that would need bringing up, would you? And yet, again and again we see poorly-lit paranormal advocates stumbling all over our televisions.

Nearly every ghost-themed TV show has several scenes in which the investigators walk around a darkened place, usually at night, looking for ghosts. Purposely conducting an investigation in the dark is the equivalent of tying an anvil to a marathon runner’s foot. … If the purpose of the investigation is to get spooky footage, turn the lights off. If the purpose is to scientifically search for evidence of ghosts, leave the lights on.1

Given the silliness of these nighttime shenanigans, and given the generations of scientific skeptics to toil in this field before us, it may not surprise you that this suggestion has come up before. Father Carlos M. de Heredia was a practicing Jesuit priest from Mexico, a magician, a well known skeptic of the early twentieth century, and a respected colleague of the other skeptics of his period. He was cited by Harry Houdini,2 exposed mediumistic trickery for Popular Mechanics,3 and wrote an insightful, aptly-titled 1922 English-language debunking book, Spiritism and Common Sense. He also felt that light was good for seeing.

Good light is certainly necessary for good observation. That requisite is missing. The theories of the scientific observer may come from inspiration, but surely his knowledge comes through the senses. The light in such cases is not conducive to the accuracy of visual observation at least. And when the séance is held in the dark, as often, there is no observation, no careful scrutiny at all.4

Which of course is very often deliberate. For all the patter and lore and traditions that justify wide-eyed attention in the dark, the underlying reasons for darkness in séances and ghost-hunts and Bigfoot wrangling is that this condition gives reign to the imagination—and permits and conceals trickery. As Father Heredia explained, “The strangeness of atmosphere—a factor entirely absent from the ordinary investigations of the scientific observer—tends to increase his emotional sensitiveness. That feeling of mystery, of something extraordinary about to occur, influences his disposition to see and believe the mysterious and extraordinary.”

The persuasive effect of the cloak of darkness, as David Phelps Abbott explained in his famous 1907 exposé Behind the Scenes with the Mediums, was an innovation of nineteenth century tricksters, a fashion that was picked up and spread:

The next fashion was the dark seance. This always seemed so unreasonable to me, and such evidence of trickery, that I have always been surprised that otherwise intelligent persons could give credence to such performances.5

Unreasonable, perhaps. And yet darkness worked then, and works now, and has worked for a very long time. Here is how Lucian of Samosata described the stage-setting for Alexander the Oracle-monger, almost two thousand years ago:

“Now then, please imagine a little room, not very bright and not admitting any too much daylight…”6

References

- Radford, Benjamin. Scientific Paranormal Investigation: How to Solve Unexplained Mysteries. (Rhomus Publishing Company: Corrales, 2010.) p. 125

- Houdini, Harry. A Magician Among the Spirits. (Fredonia Books: Amsterdam, 2002.) p. 114

- “Spirit Hands, ‘Ectoplasm,’ and Rubber Gloves.” Popular Mechanics. Vol. 40, No. 1. July 1923. pp. 14–15.

- C. M. de Heredia. Spiritism and Common Sense. (New York: P. J. Kenedy & Sons, 1922.) p. 46

- Abbot, David Phelps. Behind the Scenes with the Mediums. (Chicago: The Open Court Publishing Co., 1907.) pp. 53–54

- Lucian. A. M. Harmon, trans. Lucian. Vol IV. (London: William Heinemann, 1961). p. 197–199